Russians in the Baltic states

Russians in the Baltic states is a broadly defined subgroup of the Russian diaspora who self-identify as ethnic Russians, or are citizens of Russia, and live in one of the three independent countries — Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania — primarily the consequences of the USSR's forced population transfers during occupation. As of 2023, there were approximately 887,000 ethnic Russians in the three countries (296,000 in Estonia, 445,000 in Latvia and 145,000 in Lithuania),[1][2][3] having declined from ca 1.7 million in 1989,[4] the year of the last census during the 1944–1991 Soviet occupation of the three Baltic countries.

History

[edit]Most of the present-day Baltic Russians are migrants from forcible population transfers in the Soviet occupation era (1944-1991) and their descendants[5], though a relatively small fraction of them can trace their ancestry in the area back to previous centuries.

According to official statistics, in 1920, ethnic Russians (most of them residing there from the times of the Russian Empire) made up 7.82% of the population in independent Latvia, growing to 10.5% in 1935.[6] The share of ethnic Russians in the population of independent Estonia was about 8.2%, of which about half were indigenous Russians living in the areas in and around Pechory and Izborsk which were added to Estonian territory according to the 1920 Estonian-Soviet Peace Treaty of Tartu, but were transferred to the Russian SFSR by the Soviet authorities in 1945. The remaining Estonian territory was 97.3% ethnically Estonian in 1945. The share of ethnic Russians in independent Lithuania (not including the Vilnius region, then annexed by Poland) was even smaller, about 2.5%.[7]

The Soviet Union invaded and occupied and subsequently annexed Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania as Soviet republics in 1940. Germany invaded and occupied the Baltic states in 1941 a week after the first Soviet-conducted mass deportation. Communist party members who had arrived in the area with the initial annexation in 1940 and the puppet regimes established evacuated to other parts of the Soviet Union; those who fell into German hands were treated harshly or murdered. The Soviet Union reoccupied the Baltic states in 1944–1945 as the war drew to a close. The USSR relied on violence, torture, rape in order to subjugate the local Baltic populations.[8]

Immediately after the war, a major influx from other USSR republics primarily of ethnic Russians took place in the Baltic states as part of a de facto process of Russification. These new migrants supported the industrialization of Latvia's economy. Most were factory and construction workers who settled in major urban areas. The influx included the establishment of military bases and associated personnel with the Baltic states now comprising the USSR's de facto western frontier bordering the Baltic Sea. Many military chose to remain upon retirement, attracted by higher living standards as compared to the rest of the USSR. This led to bitter disputes with Russia regarding the issue of their military pensions after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

After Stalin's death in 1953, the flow of new migrants to the Lithuanian SSR slowed down, owing to different policies on urbanization, economics and other issues then pursued in the Latvian SSR and the Estonian SSR.[7] However, the flow of immigrants did not stop entirely in Lithuania, and there were further waves of Russian workers who came to work on major construction projects, such as power plants.[citation needed]

In Latvia and Estonia, less was done to slow down Russian immigration. By the 1980s Russians made up about third of the population in Estonia, while in Latvia, ethnic Latvians made up about half of the population. In contrast, in 1989 only 9.4% of Lithuania's population were Russians.[citation needed]

Scholars in international law have noted that "in accordance with Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, the settlement of Russians in the Baltic States during the period was illegal under international law" ("The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies").[9][10][11] The convention was adopted in 1949, including by the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union falsely claimed that the Baltic States joined the USSR voluntarily, and that it did not consider the convention applicable to the Baltic states — rhetoric that Putin's Russia continues to repeat today. [12]

Continuing the position of their legations or governments in exile, and based on international law and treaties in effect at the time of initial Soviet occupation, the Baltic states view the Soviet presence in the Baltic states as an illegal occupation for its full duration. This continuity of the Baltic states with their first period of independence has been used to re-adopt pre-World War II laws, constitutions, and treaties and to formulate new policies, including in the areas of citizenship and language.

Some of the Baltic Russians, mainly those who had come to live in the region not long before the three countries regained independence in 1991, remigrated to Russia and other ex-Soviet countries in the early 1990s. Lithuania, which had been influenced by immigration the least, granted citizenship automatically. In Latvia and Estonia, those who had no family ties to Latvia prior to World War II did not receive automatic citizenship. Those that failed to request Russian citizenship during the time window it was offered were granted permanent residency "non-citizen" status. (see Citizenship section).

Current situation

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (April 2024) |

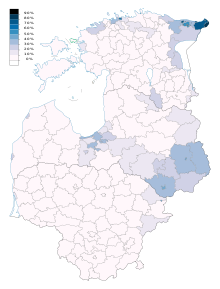

Lithuanian Russians live mainly in cities. In the Lithuanian capital Vilnius, they make up less than 10% of the population, in Lithuania's third largest city Klaipėda less than 20%. Other Lithuanian cities, including the second-largest city Kaunas, have lower percentages of Russians, while in most small towns and villages there are very few Russians (with the exception of Visaginas). In all, 5% of Lithuania's population are ethnic Russians.[13]

Russians make up around one third of the population of Latvia's capital, Riga. In the second largest city Daugavpils, where already before World War I Russians were the second biggest ethnic group after Jews,[14] Russians now make up the majority. Today about 25% of Latvia's population are ethnic Russians.

In Estonia, Russians are concentrated in urban areas, particularly in Tallinn and the north-eastern county of Ida-Virumaa. As of 2011, 38.5% of Tallinn's population were ethnic Russians and an even higher number – 46.7% spoke Russian as their mother tongue.[15] In 2011, large proportions of ethnic Russians were found in Narva (82%),[16] Sillamäe (about 82%)[17] and Kohtla-Järve (70%). In the second largest city of Estonia – Tartu – ethnic Russians constitute about 16% of the population.[18] In rural areas the proportion of ethnic Russians is very low (13 of Estonia's 15 counties are over 80% ethnic Estonian). Overall, ethnic Russians make up 24% of Estonia's population (the proportion of Russophones is, however, somewhat higher, because Russian is the mother tongue of many ethnic Ukrainians, Belarusians and Jews who live in the country).

Demand for industrial workers drew Russians to settle in larger cities. In all three countries, the rural settlements are inhabited almost entirely by the main national ethnic groups, except some areas in eastern Estonia and Latvia with a longer history of Russian and mixed villages. The Lithuanian city of Visaginas was built for workers at the Ignalina nuclear power plant and therefore has a Russian majority. A 2014 study found that many Russians identified with the place where they lived.[19]

After the accession of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania to the European Union on 1 May 2004, many Baltic Russians moved to other EU countries. In particular, tens of thousands of Baltic Russians (especially those with EU citizenship) moved to the United Kingdom and to Ireland, who were the first 'old' EU countries to open up their labour markets to the new members of the EU. Thousands of Russians from Riga, Tallinn and Vilnius, holding EU passports, now live in London, Dublin and other cities in the UK and Ireland.[citation needed][20] They make up a substantial part of the Russian-speaking community in London.[citation needed] No reliable statistics on their exact numbers exist, as in the UK they are counted as nationals of the Baltic countries, and not as Russians.

In 2012, Dimitri Medvedev issued a repatriation program designed to resettle ethnic Russians from abroad. So far 10,000[specify] families have settled in the Russian Federation, mostly to Pskov Oblast.[citation needed]

Citizenship

[edit]After regaining independence in 1991, Latvia and Estonia restored the pre-1940 citizenship laws on the basis of the legal continuity of their statehood throughout 1940 – 1991, automatically recognising citizenship according to the principle of jus sanguinis for the persons who held citizenship before 16 June 1940 and their descendants. Most of those who had settled on the territory of these republics after their incorporation by the USSR of these states by the USSR in 1940 and their descendants received the right to obtain citizenship through naturalisation procedure, but were not granted citizenship automatically. This policy affected not only ethnic Russians, but also the descendants of those ethnic Estonians and Latvians who emigrated from these countries before independence was proclaimed in 1918. Dual citizenship is also not allowed, except for those who acquired citizenship by birth.

Knowledge of the respective official language and in some cases the Constitution and/or history and an oath of loyalty to established constitutional order was set as a condition for obtaining citizenship through naturalisation. However, the purported difficulty of the initial language tests became a point of international contention, as the government of Russia, the Council of Europe, and several human rights organizations claiming that they made it impossible for many older Russians who grew up in the Baltic region to gain citizenship. As a result, the tests were altered,[21][citation needed] but a large percentage of Russians in Latvia and Estonia still have non-citizen or alien status. Those who have not applied for citizenship feel they are regarded with suspicion, under the perception that they are deliberately avoiding naturalisation.[citation needed] For many, an important reason not to apply for citizenship is the fact that Russia gives non-citizens preferential treatment: they are free to work[22] or visit relatives in Russia. The citizens of the Baltic states must apply for visas.

The language issue is still contentious, particularly in Latvia, where there were protests in 2003 and 2004 organized by the Headquarters for the Protection of Russian Schools against the government's plans to require at least 60% of lessons in state-funded Russian-language high schools to be taught in Latvian.[23][24]

In contrast, Lithuania granted citizenship to all its residents at the time of independence redeclaration day willing to have it, without requiring them to learn Lithuanian. Probably the main reason that Lithuania took a less restrictive approach than Latvia and Estonia is that whereas in Latvia ethnic Latvians comprised only 52% of the total population, and in Estonia ethnic Estonians comprised barely more than 61%, in Lithuania ethnic Lithuanians were almost 80% of the population.[4] Therefore, as a matter of voting in national elections or referendums, the opinions of ethnic Lithuanians would likely carry the day if there were a difference in opinion between Lithuanians and the larger minority groups (Russians and Poles), but this was less certain in the other two Baltic countries, especially in Latvia.

Some representatives of the ethnic Russian communities in Latvia and Estonia have claimed discrimination by the authorities, these calls frequently being supported by Russia. On the other hand, Latvia and Estonia deny discrimination charges and often accuse Russia of using the issue for political purposes.[25] In recent years, as the Russian political leaders have begun to speak about the "former Soviet space" as their sphere of influence,[26] such claims are a source of annoyance, if not alarm, in the Baltic countries.[25][27]

Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania have since 2004 become members of NATO and the European Union (EU) to provide a counterbalance to Russia's claims to speak for the interests of ethnic Russian residents of these countries. Furthermore, to satisfy a precondition for their admission to the EU, both Estonia and Latvia slightly adjusted their citizenship policies in response to EU monitoring and requests.[citation needed]

Political activity

[edit]

There are a number of political parties and politicians in the Baltic states who claim to represent the Russian-speaking minority. These parties support Russian language rights, demand citizenship for all long-term residents of Latvia and Estonia. These forces are particularly strong in Latvia represented by the Latvian Russian Union which has one seat in the European Parliament held by Tatjana Ždanoka and the more moderate Harmony party which is currently the largest faction in the Saeima with 24 out of 100 deputies, the party of the former Mayor of Riga Nils Ušakovs and with one representative in the European Parliament currently Andrejs Mamikins. In Estonia the Estonian Centre Party is overwhelmingly the most favored party among Estonian Russians. This is in part because[28][29] of its co-operation agreement with United Russia, its advocacy of friendlier ties with the Russian government compared to other mainstream Estonian parties and the prevalence of[citation needed] Russians and Russophones among the party's municipal councilors and parliamentarians.

In 2011 pro-Russian groups in Latvia collected sufficient signatures to initiate the process of amending the Constitution to give Russian the status of an official language. On 18 February 2012, constitutional referendum on whether to adopt Russian as a second official language was held.[30] According to the Central Election Commission, 74.8% voted against, 24.9% voted for and the voter turnout was 71.1%.[31] The non-citizen community (290,660 or 14.1% of Latvia's entire population) was non-entitled to vote.

Notable Baltic Russians

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

Famous modern Baltic Russians include:

- Mikhail Baryshnikov, Russian-American dancer and actor, born in Riga[32]

- Ludmilla Chiriaeff, ballet dancer, choreographer, and director, born in Riga[33]

- Mikhail Eisenstein, architect designer of many buildings in Riga, father of Sergei Eisenstein, born in Riga

- Sergei Eisenstein, director who made some famous Russian films (including The Battleship Potemkin), born in Riga[34]

- Alexandr Kaleri, Russian cosmonaut born in Jūrmala

- Valeri Karpin, football midfielder, born in Narva

- Alexander Kovalevsky, embryologist born near Daugavpils

- Alexei Kudrin, former Russian finance minister born in Dobele[35]

- Evgenii Miller, Russian general born in Daugavpils

- Marie N (Marija Naumova), winner of the 2002 Eurovision Song Contest for Latvia

- Nikolai Novosjolov, an Estonian fencer[36]

- Nikita Ivanovich Panin, Russian 18th century statesman from Pärnu

- Vladimirs Petrovs, chess player, born in Riga

- Roman Romanov, businessman and former Chairman of Heart of Midlothian F.C.

- Vladimir Romanov, businessman and former owner of Heart of Midlothian F.C. football club, citizen of Lithuania

- Uljana Semjonova, basketball player from Daugavpils

- Alexei Shirov, chess grandmaster born in Riga

- Konstantin Sokolsky, singer from Riga

- Anatoly Solovyev, pilot and cosmonaut, born in Riga[37]

- Aleksandrs Starkovs, Latvia national football team coach of 2001–2004

- Yury Tynyanov, writer, literary critic, translator, scholar and scriptwriter born in Rēzekne[38]

- Nils Ušakovs, former mayor of Riga[39]

- Viktor Uspaskich, former leader of the Lithuanian Labour Party, former Lithuanian minister of the economy, former member of the Lithuanian parliament, the Seimas, and the current member of the European Parliament elected from Lithuania

- Mikhail Nikolayevich Zadornov, Latvian-born Russian comedian

- Tatjana Ždanoka, former member of the European Parliament elected from Latvia

- Sergejs Žoltoks, professional ice hockey player from Riga

- Artjoms Rudņevs, football player from Daugavpils

- Teodors Bļugers, ice hockey player from Riga

See also

[edit]- History of Russians in Estonia

- History of Russians in Latvia

- History of Russians in Lithuania

- Ethnic Russians in post-Soviet states

References and notes

[edit]- ^ "RL21429: POPULATION BY ETHNIC NATIONALITY, SEX, AGE GROUP AND PLACE OF RESIDENCE (ADMINISTRATIVE UNIT), 31 DECEMBER 2021". PxWeb. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Iedzīvotāji pēc valstiskās piederības un dzimšanas valsts gada sākumā 2011 - 2023". Oficiālās statistikas portāls (in Latvian). Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Rodiklių duomenų bazė - Oficialiosios statistikos portalas". osp.stat.gov.lt. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Демоскоп Weekly - Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей". www.demoscope.ru. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Idzelis, Augustine (1985). "Soviet Russian Colonial Practices in the Baltic states". In Pap, Michael S. (ed.). Russian Empire: some aspects of tsarist and Soviet colonial practices. John Carroll University. Institute for Soviet and East European Studies. p. 79.

- ^ "Data on population of Latvia in 1920–1935".

- ^ a b Vaitiekūnas, Stasys, Lietuvos gyventojai per du tūkstantmečius

- ^ "How Russian Disinformation Targets the Former Soviet Bloc Around WWII Anniversaries - CHACR". 6 July 2020.

- ^ Ronen, Yaël (2011). Transition from Illegal Regimes Under International Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 206.

- ^ Benvenisti, Eyal (1993). The International Law of Occupation. Princeton University Press. pp. 67–72.

- ^ "ICRC".

- ^ "How Russian Disinformation Targets the Former Soviet Bloc Around WWII Anniversaries - CHACR". 6 July 2020.

- ^ "Rodiklių duomenų bazė – Oficialiosios statistikos portalas".

- ^ "Демоскоп Weekly – Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей".

- ^ "Statistical yearbook of Tallinn".

- ^ "Narva in figures" (PDF).

- ^ "Sillamae". 2010. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013.

- ^ "Tartu arvudes" (PDF).

- ^ Matulionis, Arvydas Virgilijus; Frėjutė-Rakauskienė, Monika (2014). "Идентичность русской этнической группы и ее выражение в Литве и Латвии. Сравнительный аспект" [Identity of ethnic Russians in Lithuania and Latvia] (in Russian). Mir Rossii.

- ^ Aptekar, Sofya (1 December 2009). "Contexts of Exit in the Migration of Russian Speakers from the Baltic Countries to Ireland". Ethnicities. 9 (4): 507–526. doi:10.1177/1468796809345433. PMC 3868474. PMID 24363609.

- ^ Heleniak, Timothy (1 February 2006). "Latvia Looks West, But Legacy of Soviets Remains". Migration Policy Institute. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Russia has started issuing 'non-citizen passports.' What does that mean?". Meduza. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Eglitis, Aaron (11 September 2003). "Protesters rally against education reform". The Baltic Times. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- ^ Eglitis, Aaron (29 January 2004). "School reform amendment sparks outrage". The Baltic Times. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- ^ a b Vohra, Anchal (22 May 2024). "Latvia Is Going on Offense Against Russian Culture". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Vladimir Socor, Kremlin Refining Policy in 'Post-Soviet Space' Archived 3 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Eurasia Daily Monitor 8 February 2005

- ^ Higgins, Andrew (18 December 2023). "In a Baltic Nation, Fear and Suspicion Stalk Russian Speakers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Martyn-Hemphill, Richard (21 November 2016). "Estonia's New Premier Comes From Party With Links to Russia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ ERR (8 November 2016). "Overview: Center Party's cooperation protocol with Putin's United Russia". ERR. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Referendum on the Draft Law 'Amendments to the Constitution of the Republic of Latvia'". Central Election Commission of Latvia. 2012. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ "Results of the referendum on the Draft Law 'Amendments to the Constitution of the Republic of Latvia'" (in Latvian). Central Election Commission of Latvia. 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ "Mikhail Baryshnikov | Biography, Movies, Dancing, Sex and the City, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Ludmilla Chiriaeff". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Sergei Eisenstein | Biography, Films, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 29 February 2024. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Ministry Of Finance Of The Russian Federation". Archived from the original on 14 February 2010.

- ^ "INTERNATIONAL FENCING FEDERATION - The International Fencing Federation official website". FIE.org. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Rīgā viesosies kosmonauts Anatolijs Solovjovs". Latvijā (in Latvian). 7 March 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Tynyanov, Yuri Nikolayevich". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "10 facts about Mayor of Riga Nils Ušakovs — RealnoeVremya.com". m.realnoevremya.com. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Benedikter, Thomas, ed. (2008). "Nationality-based exclusion: the Russians in the Baltic states". Europe's Ethnic Mosaic. A Short Guide to Minority Rights in Europe. Accademia Europea Bolzano. pp. 66–69.

- Cheskin, Ammon. "Identity and integration of Russian speakers in the Baltic States: A framework for analysis." Ethnopolitics 14.1 (2015): 72–93. online

- Cheskin, Ammon, and Angela Kachuyevski. "The Russian-speaking populations in the post-Soviet space: language, politics and identity." Europe-Asia Studies 71.1 (2019): 1-23. online

- Cheskin, Ammon. Russian-Speakers in Post-Soviet Latvia: Discursive Identity Strategies (Edinburgh University Press, 2016).

- Kallas, Kristina. "Claiming the diaspora: Russia's compatriot policy and its reception by Estonian-Russian population." Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe (JEMIE) 15 (2016): 1+. online

- Kirch, Aksel, Marika Kirch, and Tarmo Tuisk. "Russians in the Baltic States: To be or not to be?." Journal of Baltic Studies 24.2 (1993): 173–188. in JSTOR

- Laitin, David D. "Three models of integration and the Estonian/Russian reality." Journal of Baltic Studies 34.2 (2003): 197–222.

- Lane, Thomas. Lithuania: stepping westward (Routledge, 2014).

- Naylor, Aliide. 'The Shadow in the East: Vladimir Putin and the New Baltic Front' (I.B. Tauris, 2020)

- Schulze, Jennie L. Strategic frames: Europe, Russia, and minority inclusion in Estonia and Latvia (U of Pittsburgh Press, 2018).

- Shafir, Gershon. Immigrants and nationalists: Ethnic conflict and accommodation in Catalonia, the Basque Country, Latvia, and Estonia (SUNY Press, 1995).

- "Russians". EU-MIDIS. European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey. Main Results Report (PDF). Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union. 2010. pp. 176–195. ISBN 978-92-9192-461-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2010. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- Russian Minorities in the Baltic States "Ethnicity" No. 3/2010 ISSN 1691-5844